There is a long tradition in politics of disguising controversial policies with innocuous or even positive-sounding names. In 2001, President George W. Bush named his primary education initiative the No Child Left Behind Act (NCLB), a title that, on its face, has universal appeal. In reality, NCLB enacted a highly contentious standardized testing regime that critics of the law contend left more than a few children behind.

More recently, during the high-prices era of the early-2020s, President Biden signed the 2022 Inflation Reduction Act. Not only did the law fail to reduce inflation, according to the Congressional Budget Office, it also added more than $700 billion in new spending to the U.S. economy.

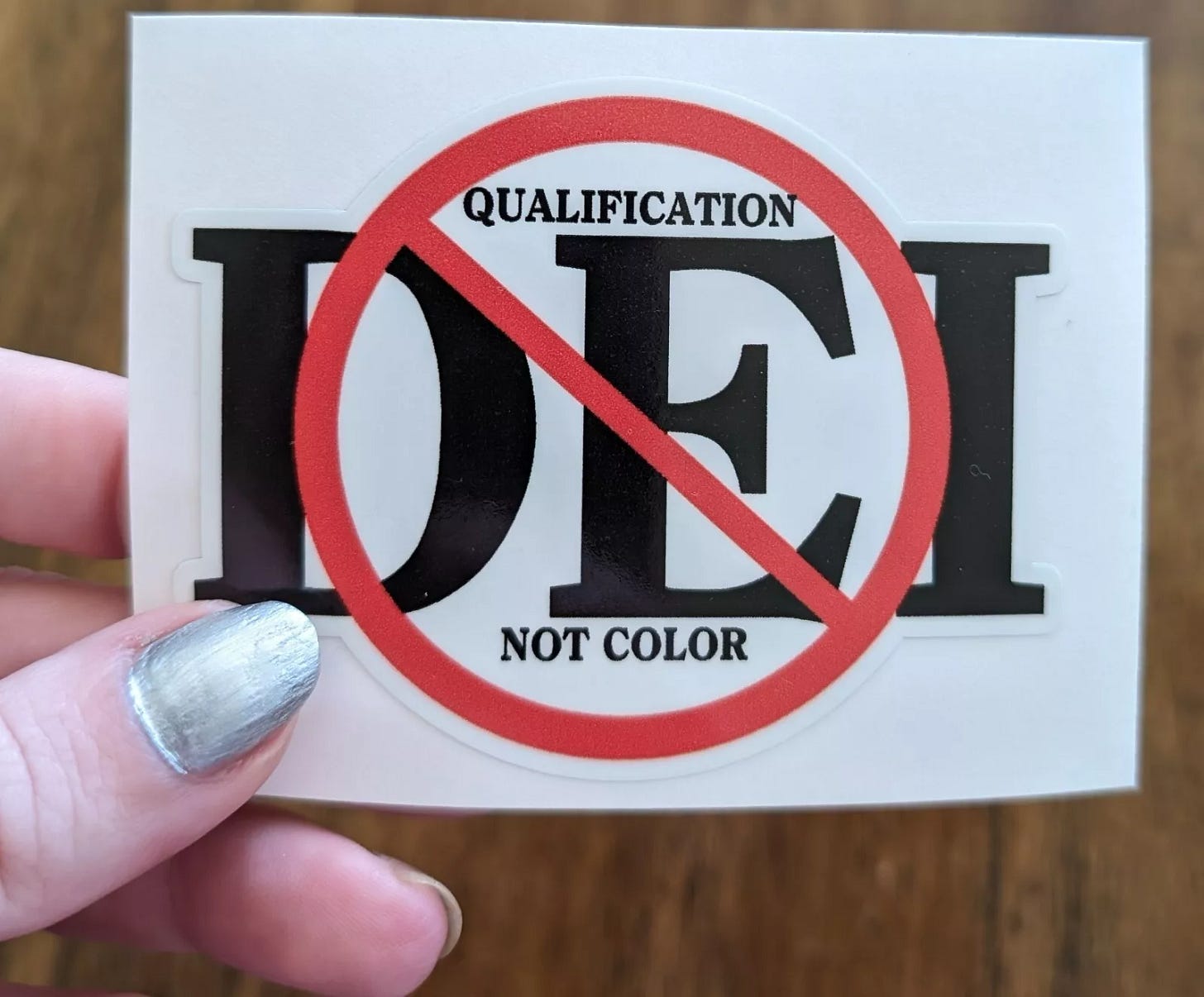

The most recent misleadingly named, polarizing program to enter the national spotlight is Diversity, Equity and Inclusion, better known as DEI, a collection of policies and that are designed to remedy past injustice by extending certain advantages to groups that, historically, have faced disadvantages. President Trump has systematically targeted these policies in the public sector, through a series of executive orders, and in the private sector, by applying pressure to American companies and fostering a climate that is hostile to DEI.

Trump’s actions have been one of a partisan. Killing DEI and other progressive, identity-based programs has been a top Republican goal for at least a decade, not only because Republicans oppose these programs on principle, but because they fear that DEI indoctrination will make people vote Democrat.

Yet, anti-partisanism also rejects DEI and related programs, even though anti-partisanism affirms the importance of diversity and inclusion (“equity” is a loaded term). Anti-partisanism holds that the basis for universal equality is the common, human DNA in all people. Our shared humanity is what unites us as equals. However, this idea clashes with modern notions of justice, which are centered around identity groups.

DEI is actually one of several offshoots of an umbrella concept that is sometimes as known as “social justice” or, in common usage, “wokeness.” In elementary terms, social justice views life through the prism of power relationships between different groups (e.g. race; ethnicity; gender; sexuality) and seeks to alter perceived imbalances in these relationships.

“Social justice,” like DEI (its workplace and campus incarnation), is one of those terms that sounds indisputably noble, which contributes to its flattering press coverage. This is also the case for “anti-racism,” its more recent, race-based incarnation, which is sometimes bunched in with the more dryly named, academic concept of critical race theory (CRT). Ditto for “Environmental, Social and Governance,” (ESG) which involves evaluating the “social responsibility” of businesses based on their adherence to social justice principles.

Social justice is essentially a 21st-century rebranding and expansion of the late-20th-century political correctness movement. And, just as is true of political correctness, the intellectual foundations for social justice were established in higher education.

Universities have long sought to be forces for positive change, but their efforts to this end have evolved over time. In the prior century, at least at the institutional level, schools focused on producing difference-makers among their graduates and taking uncontroversial stances, such as opposing South African apartheid.

However, as the turn-of-the-century approached, schools expanded the do-gooder aspect of their mission and started to publicly take sides (i.e. the left side) on hotly disputed issues. Pushed by activist-minded faculty, this effort began with the creation of campus speech codes that aimed to restrict the use of terms that were deemed offensive, a primary component of the political correctness movement. Courts invalidated some of these codes, somewhat limiting their reach, but their undergirding philosophy only became more ingrained in the university psyche.

But, there are substantial variations between the two movements. While the original political correctness movement was centered on prescribing speech, social justice is centered on prescribing thought. To be aligned with political correctness in the last century was to use the appropriate “P.C.” terminology when talking about issues pertaining to people from different groups. To be aligned with social justice in this century is to hold the appropriate “socially just” ideas about issues pertaining to people from different groups.

Also, the original campus political correctness movement was primarily driven by faculty. However, when it reemerged as social justice, its resurgence was initially spearheaded by administrators, although students soon raced past them to the front lines of the crusade.

Twenty-first-century students also helped spread social justice culture beyond campus after they left. Some got jobs in fields like management and human resources where they could directly influence company culture, gradually making the embrace of social justice-aligned policies into a business trend. Others obtained positions in education, legal or communications-oriented fields, where their endeavors increased the momentum of the direction those fields were already heading, following higher education’s lead. And others exerted pressure from the bottom, leveraging companies’ need to hire younger employees to shape the culture of their workplaces to their liking, including influencing their employers to adopt social justice principles.

The significance of this shift is difficult to exaggerate, as a social justice- mindset now dominates not just education but the rest of the professional world too. First, schools redefined and expanded their missions through their acute focus on social justice, which essentially changed the character of college. It was only natural, then, for kindred fields to follow the lead of higher education. Finally, real world events, such as mass shootings and killings of people of color by police, pushed most of the remainder of the business world in that direction.

But, social justice’s permeation of society doesn’t stop at schools and offices. The worlds of Hollywood, music, sports and culture regularly show their solidarity with the movement through the content of their art, their public statements and social media posts, and their activism.

Seen in this light, it would appear as if Americans have embraced social justice as our national creed. Baseball, mom and apple pie…and wokeness.

But, polls have shown that a clear majority opposes bedrock social justice ideas. For example, a 2021 Economist/YouGov poll found that 58% of Americans who are acquainted with critical race theory see it negatively, compared to 36% who view it positively. And a 2021 Yahoo News/YouGov poll revealed that two-thirds of Americans believe political correctness is a “large” or “somewhat large” problem, about as many as said the same about Covid. Further, the amount of people who thought political correctness was a large problem (39%) in the survey—which was taken in the middle of the pandemic—was significantly larger than the amount who thought the same of Covid (32%).

And, even among folks who outwardly back social justice, some of them are simply conforming to social pressure. According to the Cato Institute’s 2017 Free Speech and Tolerance Survey, when it comes to expressing their political beliefs in public, 58% of Americans self-censor due to the “political climate.” Hence, we can infer that a sizable number of individuals are just keeping their heads down during mandatory “diversity training” workshops and simply regurgitating the expected responses, instead of sharing their true opinions on the subject matter.

CRT and political correctness are only elements of social justice, and other aspects, such as racial justice protests, poll higher. Yet, the polling on this pair of ideas is nonetheless a reliable gauge of support for social justice. Because CRT and, especially, political correctness define the movement’s most practical essence: to prescribe language and thought about issues relating to select groups and to suppress dissent on those topics.

Now, social justice perfectly illustrates the anti-partisan tenet that people’s political beliefs come from a good place. Trying to lessen inequalities between different groups, as social justice does, is good.

But, social justice doesn’t just aspire to lessen inequality but to invert it. After all, defenders argue, because some groups (i.e. white, male, heterosexual, Christian etc.) have historically had a monopoly of power and privilege, perhaps it would be socially just for this hierarchy to be flipped.

However, justice is not a finite resource that needs to be redistributed in order to be doled out in equal measure. Justice wasn’t equally dispensed in the past, and it may not even fully be now, but that isn’t a call to try to compensate by reversing how it’s apportioned now. The appropriate way to tackle inequalities is to eliminate them, not invert them. Certain groups don’t have to fall in order for others to rise.

No, anti-partisanism doesn’t seek to rearrange the hierarchy. It seeks to demolish it.

Anti-partisanism accepts the importance of group membership to individual identity. However, it rejects social justice’s collectivist obsession with group identity, which does not allow for the equality of individuals because it permanently consigns everybody to either a class of oppressors or the oppressed.

Also, one of the most problematic aspects of social justice theory is that it contains nothing for stakeholders whom it doesn’t define as oppressed. Whereas anti-partisans value and seek to serve every stakeholder, social justice proponents, like partisans, simply pick and choose whose stakes matter to them (i.e. the oppressed).

In fact, when stakeholders whom social justice doesn’t acknowledge assert their stakes, the movement’s advocates have a term for it. According to author Robin DiAngelo, any opposition to social justice, either in principle or to its practical effects, can be dismissed as “white fragility,” which is the title of DiAngelo’s best-selling book, a vital component of the social justice canon.

This approach is identical to the way ardent religious followers respond to ideas that conflict with their faith. Devoted believers consider the precepts of their religions to be inerrant. Their beliefs are of divine origin and aren’t subject to rational inquiry. Instead, the beliefs themselves are cited as infallible and invoked to refute opposing ideas.

Social justice proponents react to criticism of social justice orthodoxy in kind. If the teachings of social justice are challenged, adherents rebuke the challenge by citing the teachings of social justice.

This is unsurprising since social justice itself is a simple appropriation of the fundamentalist Christian doctrine of original sin. In Christian theology, humans are born into a sinful state because the first humans, Adam and Eve, sinned by disobeying God. In order for humans’ relationship with God to be restored, Christians believe, people must be redeemed.

In social justice theology, some people are born into a state of whiteness (or maleness or straightness or Christianness), meaning they share in the responsibility for the oppressive deeds of their ancestors. They also must atone because remnants of the power and privilege that they inherited from their ancestors still endure. However, unlike traditional Christianity, through which a redemptive act (i.e. Jesus’ death and resurrection) gives people a means to be “saved” from their sinful state, social justice offers only the demand of never-ending penance for being born into the wrong demographic brackets.

Portions of this post have been adapted from my book The Anti-Partisan Manifesto: How Parties and Partisanism Divide America and How to Shut Them Down. Buy the book here. For the time being, it is only available digitally. To read, download the Kindle app to your phone, your iPad or tablet, your Kindle device or your computer.

Follow me on X at @JeffGebeau or on Facebook