An Anti-Partisan Solution to the India-Pakistan Violence

The anti-partisan issue resolution model applied to global conflicts

Global affairs in the 2020s have been dominated by a pair of military conflicts. First, Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine and the war that ensued. Second, Hamas’ 2023 strike against Israel, which resulted in Israel’s retaliatory incursion into Hamas’ home region of Gaza.

Last week, we were reminded that there are other violent hotspots in the world, namely Kashmir, the disputed Himalayan province whose control is split between India, Pakistan and China. On Wednesday, India launched missiles into Pakistani-controlled regions of Kashmir, as well as Pakistan itself, killing 31 people.

India says the targets it struck were all sites where terrorist actions against India had been planned. Pakistan called the attack an “act of war” and vowed retribution.

On Saturday, the countries agreed to a U.S.-facilitated ceasefire, albeit a tenuous one. The nations had seemed to be verging on war in the aftermath of the missile firings, with more than 100 people having been killed in cross-border shelling and shooting, as well as additional missile launches.

Wednesday’s attack was India’s retaliation for terrorist shootings last month in an Indian-controlled area of Kashmir, which killed 26 people. India says Pakistan supports terror groups who support either Pakistan itself or else Kashmiri independence, or that Pakistan at least allows such groups to operate within its borders. India has made the same accusation for decades, which Pakistan vehemently denies.

The April shootings were the most brutal attacks in Kashmir in almost a year. Last June, terrorists opened fire on a bus containing Indians who were on a Hindu pilgrimage. Nine people died in the assault, while 33 more were injured.

Less than a year before that, in November 2023, Indian and Pakistani troops exchanged gunfire and mortar shells. An Indian soldier was killed in the fighting.

Both incidents happened after the outbreaks of the wars involving Ukraine and Israel, but neither event received more than a blip of coverage in western media. Also, the India-Pakistan tensions predate the Ukraine-Russia conflict—which began when Russia occupied portions of Ukraine in 2014—by more than 65 years.

In 1947, India, which had been a British colony, was partitioned by its exiting imperial rulers into the states of India and Pakistan, which have Hindu and Muslim majorities, respectively. The division led to an enormous and bloody population transfer, as masses of Muslims in India migrated to Pakistan, while swaths of Hindus in Pakistan fled to India. More than two-million people were killed in subsequent sectarian violence.

However, the more-religiously-balanced-but-still-majority-Muslim province of Kashmir in the northeast was given the right of self-determination, having the choice between becoming part of Pakistan, becoming part of India or becoming independent.

Initially, Kashmir opted for independence. But, when Pakistani militants invaded the province in 1947, its Hindu ruler solicited Indian assistance, which India provided—in exchange for a pledge that Kashmir would join India.

That bargain led to the Indo-Pakistani War of 1947-1948. Altogether, the nations have fought four wars over Kashmir, with the most recent one having taken place in 1999.

Millions have died in the struggle to control Kashmir. And people, both military and civilian, continue to die because, in the fight for Kashmir, even interludes of “peace” have been marked by violent skirmishes that have killed thousands.

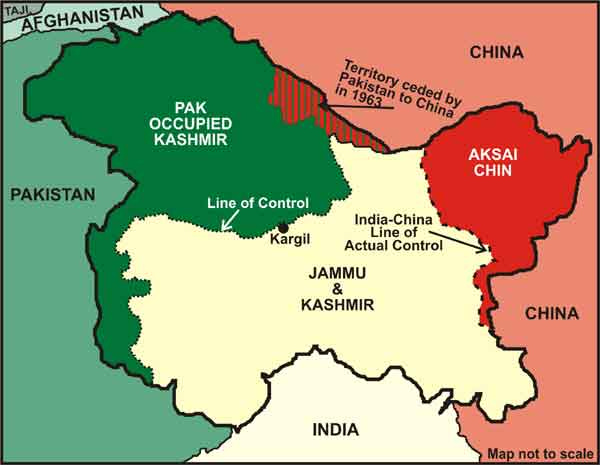

After the Indo-Pakistani War of 1971, the countries established a “Line of Control” in Kashmir, which now serves as a de facto border between the Indian and Pakistani sections of the province. Though violent tensions are a constant in the region—as the past few weeks have vividly shown—the line is still observed.

Several years later, in 1974, India developed nuclear weapons. Pakistan followed suit in 1998.

Obviously, the ultimate fear pertaining to the India-Pakistan conflict is that it could escalate to the point of nuclear strikes. Yet, the fact that both sides have nukes also deters either side from using them.

One of this site’s first pieces lays out an anti-partisan issue resolution template that can be universally applied:

Presume that people are good and come from a good place in their political beliefs

Unflinchingly establish a set of premises in each policy area

Identify the stakeholders in each policy area

Identify stakeholders’ concerns in each policy area

Seek solutions not victories

- Eliminate flashpoints for conflict

- Make recognition of the fundamental rights of stakeholders the starting point for making policy

- Validate the cares of stakeholders

This template was primarily intended to be a model for domestic policymaking, but it can also be applied to many international issues. Indians and Pakistanis can lay the groundwork for resolution of the Kashmir conflict by recognizing that their counterparts mostly consist of individuals who, at heart, are good people with valid concerns.

As far as premises, this is by no means an exhaustive list, but we can start with the facts that prior to British decolonization, the entirety of Kashmir was a territory of “British India”; yet, nevertheless, Kashmir still has a Muslim majority. Also, Pakistan has, in fact, historically given at least tacit support to Muslim militant groups who have attacked Indian parts of Kashmir, while India has used these incursions to justify harsh crackdowns against Muslims in Kashmir and the Indian mainland.

The most obvious stakeholders in the conflict are India and Pakistan. But, Kashmiri independence factions are also on the list, as is China, since it controls territory in eastern Kashmir. Then, there are the neighboring countries to India and Pakistan, who are impacted by destabilization in the region and, of course, the rest of the planet, which has a distinct interest in mitigating violent conflicts between nuclear powers.

Both countries obviously have the same goal. They both want Kashmir in its entirety, as do Kashmiri separatists.

But, beyond that aim, their objectives are more compatible. Both want their people to be able to live in peace and to be free to practice their religion, regardless of which nation or region they inhabit.

Meanwhile, China wants to retain control of the areas of Kashmir that it says were once part of Chinese kingdoms. And neighbors of India and Pakistan seek regional stability, while the rest of the world wants to avoid the threat of nuclear holocaust.

Ultimately, resolution of the Kashmir dispute can only happen in one of two ways. Either one of the countries will manage to force out the others and annex the whole province, or the nations will have to start looking at each other as partners with whom to devise a solution, rather than adversaries to defeat or outmaneuver.

But, for India and Pakistan to see each other as partners in this matter, they would have to abandon their adversarial postures toward each other. In other words, they would both have to give up their ambitions to claim the whole of Kashmir.

Thus, if the possibility of either side gaining total control of the province was taken off the table, it would remove a major flashpoint in the conflict. Because, naturally, being forced to cede the province would be the outcome that both Pakistan and India dread most.

China’s presence in Kashmir is actually beneficial in this regard. Kashmir’s trilateral rule means that it would take more than a single, decisive military campaign for Pakistan or India to be able to acquire the entire province.

In other words, seizing of all of Kashmir is a faraway dream for either nation. So, they should formally let it go by committing to a peaceful and collaborative resolution of their territorial disagreement. Call it a pre-settlement. If the nations had the wisdom and foresight to do so, it could be signed in conjunction with Saturday’s ceasefire agreement.

This preliminary pact could then become a precursor to the opening of formal treaty negotiations to resolve the Kashmir dispute. There are multiple ways that this could be handled from the enshrinement of the Line of Control to territorial purchases to land transfers to Kashmiri independence to a Kashmiri referendum.

But, whatever the shape of the final agreement, guaranteeing the rights of stakeholders must be paramount. For Indians and Pakistanis, Hindus and Muslims alike, this means having the right to live and practice their religion peacefully, wherever they live and whatever religion they practice.

Portions of this post have been adapted from my book The Anti-Partisan Manifesto: How Parties and Partisanism Divide America and How to Shut Them Down. Buy the book here. For the time being, it is only available digitally. To read, download the Kindle app to your phone, your iPad or tablet, your Kindle device or your computer.

Follow me on X at @JeffGebeau or on Facebook